Nutrient Density vs Calorie Density: Which Foods Actually Give You the Most for Your Calories?

Most people understand that some foods are “nutrient dense” and others are not. What is less commonly considered is the calorie trade off attached to those nutrients.

Two foods can both be high in iron, magnesium, zinc or calcium on paper. One might deliver that nutrient efficiently relative to calories. The other may come with a far higher energy cost.

When calories are abundant, that distinction matters less. When calories are constrained, it becomes highly relevant.

Looking at iron, magnesium, zinc and calcium plotted against calorie density highlights a useful pattern: nutrient richness and energy efficiency are not always aligned.

Thinking in Terms of Nutrient Return

One practical way to approach nutrient density is to ask a simple question:

How much of a given micronutrient does this food provide per 100 grams, and how many calories does that cost?

This does not mean every decision must be reduced to spreadsheets. It simply adds context. If someone is dieting, managing body composition, or operating within a fixed calorie intake, the concept of “nutrient return per calorie” becomes strategically important.

Across coaching practice, this is often the missing layer. People focus on macros, or on eating “clean,” but rarely assess whether their food choices are delivering meaningful micronutrients relative to their energy budget.

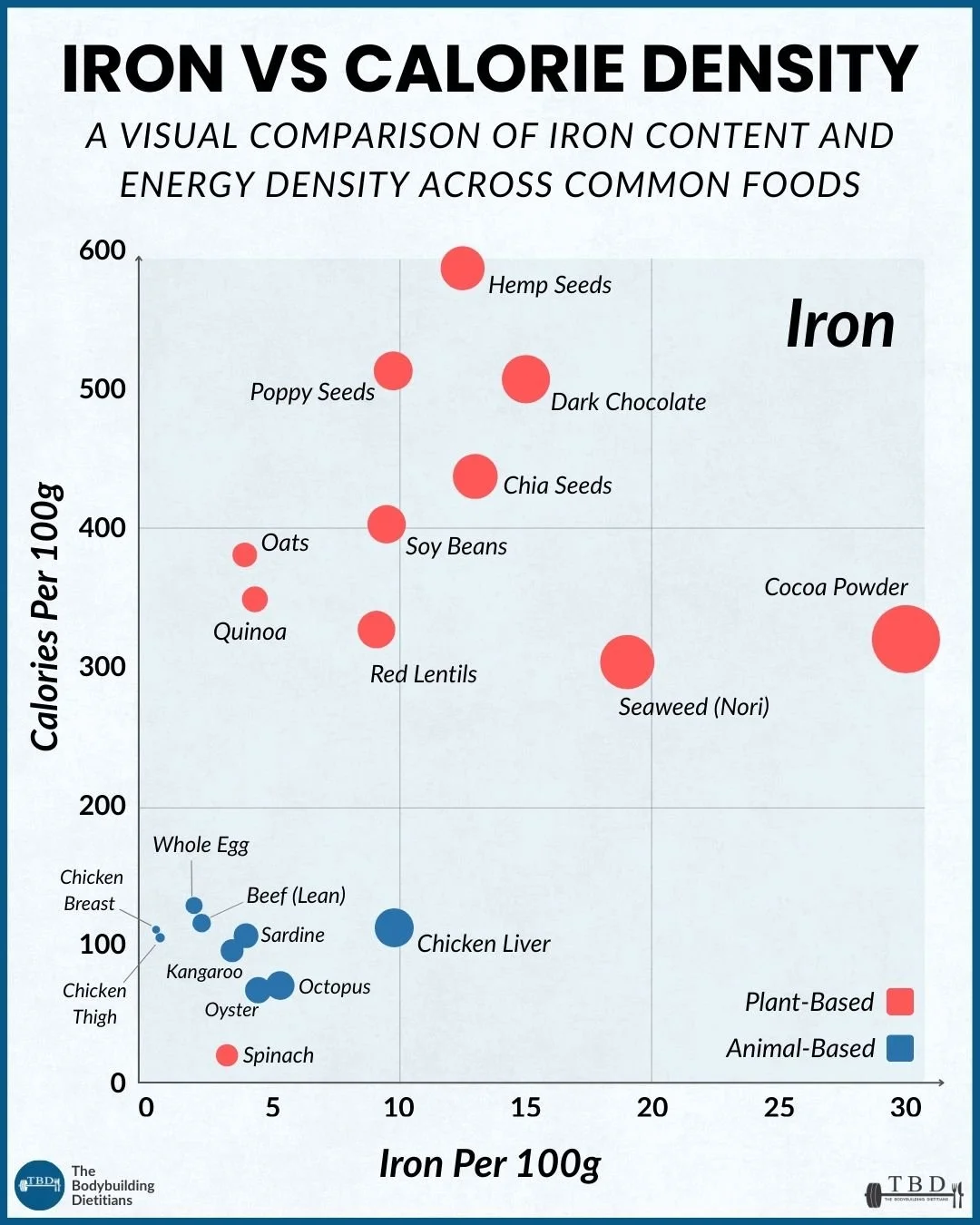

Iron: Absolute Content vs Practical Absorption

The iron comparison shows two clear clusters.

Animal based foods such as chicken liver, lean beef, sardines and oysters provide meaningful amounts of iron at relatively modest calorie levels. They tend to sit lower on the calorie density axis while still delivering solid iron content.

Plant based sources such as lentils, soybeans, cocoa powder and various seeds can also appear high in iron. However, they often come with a higher energy density.

An additional layer is bioavailability.

Heme iron from animal foods is absorbed more efficiently than non heme iron from plant foods. In practice, this means identical iron values on paper do not necessarily translate to identical physiological outcomes. Vitamin C intake, phytates, polyphenols and overall meal composition further influence absorption.

When looking at iron through an energy lens, organ meats and certain seafood options repeatedly stand out as efficient sources. Plant foods can contribute meaningfully, though the context of the overall diet matters.

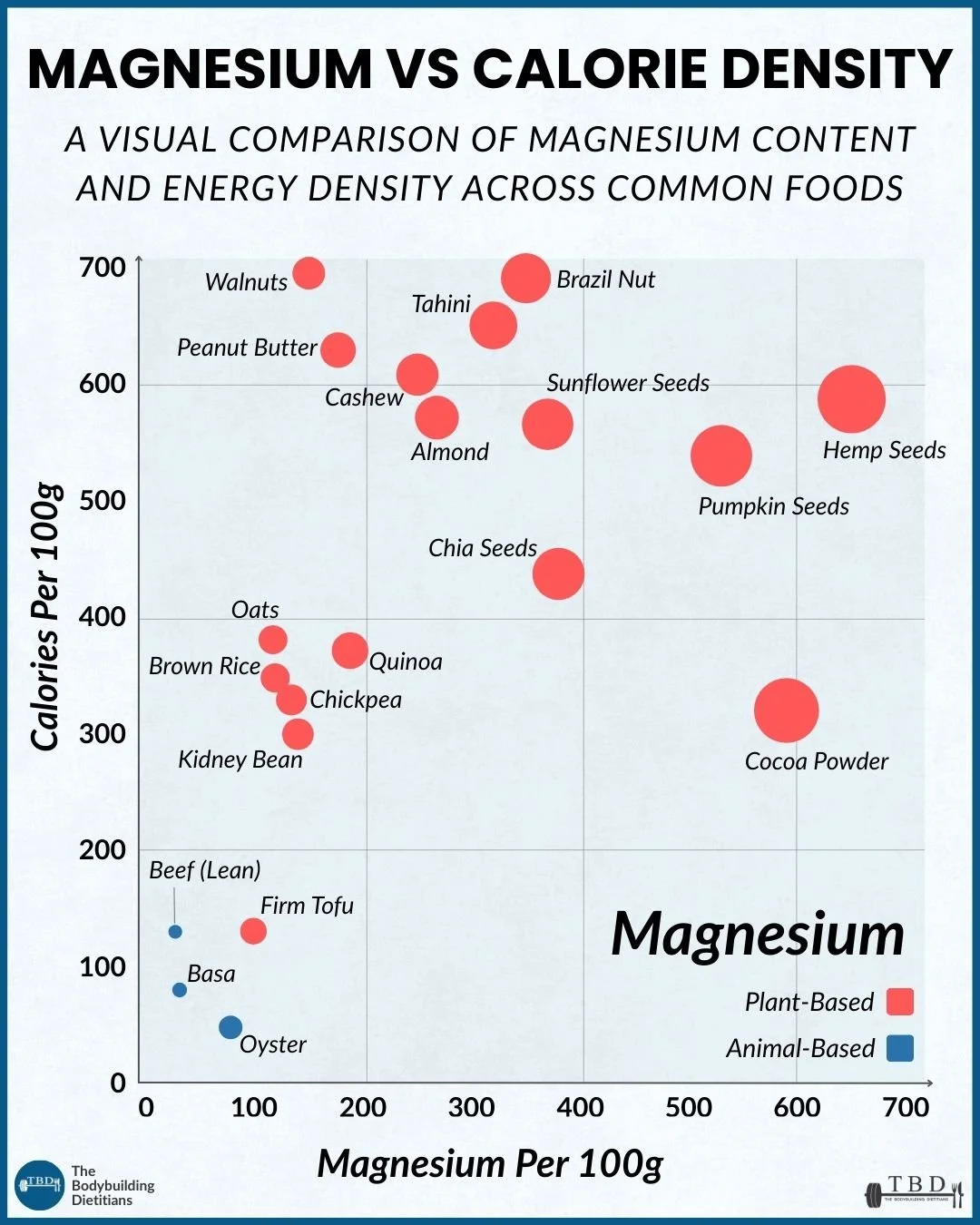

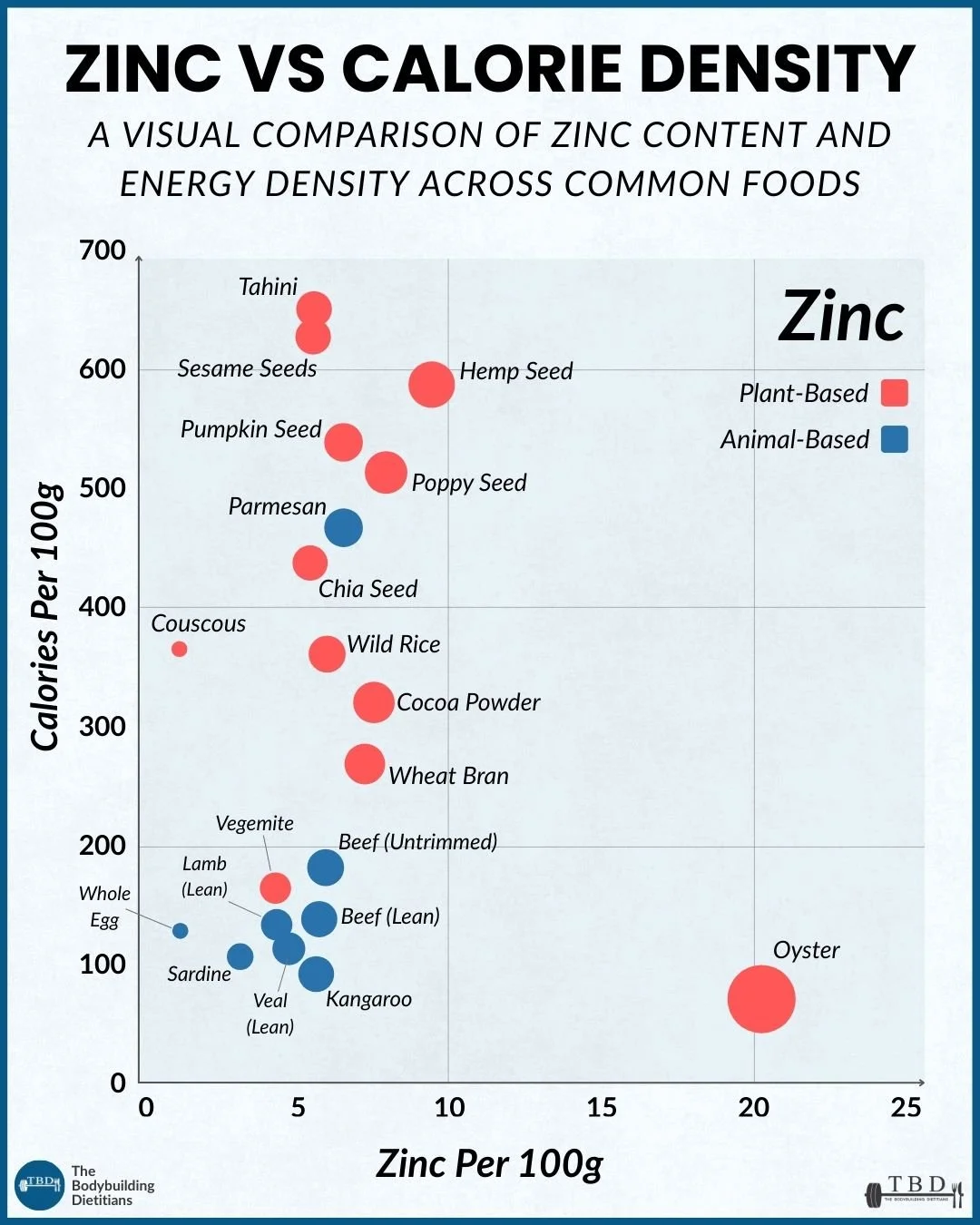

Magnesium and Zinc: Seeds and Seafood

Magnesium and zinc comparisons show a recurring pattern.

Seeds, nuts and legumes frequently rank high in absolute magnesium and zinc content. Pumpkin seeds, chia seeds, tahini, hemp seeds and almonds provide substantial amounts per 100 grams. However, these foods are also energy dense.

That does not make them poor choices. It simply means portion size matters when calorie intake is limited.

Oysters stand out clearly for zinc, delivering a large amount relative to calorie content. Certain meats also provide zinc efficiently compared to many plant options.

Again, absorption differs. Zinc uptake can be reduced in high phytate plant foods. This does not negate their value, but it adds nuance to how we interpret absolute numbers.

In practice, combining animal and plant sources, or pairing plant foods with strategies that improve absorption, often provides a balanced approach.

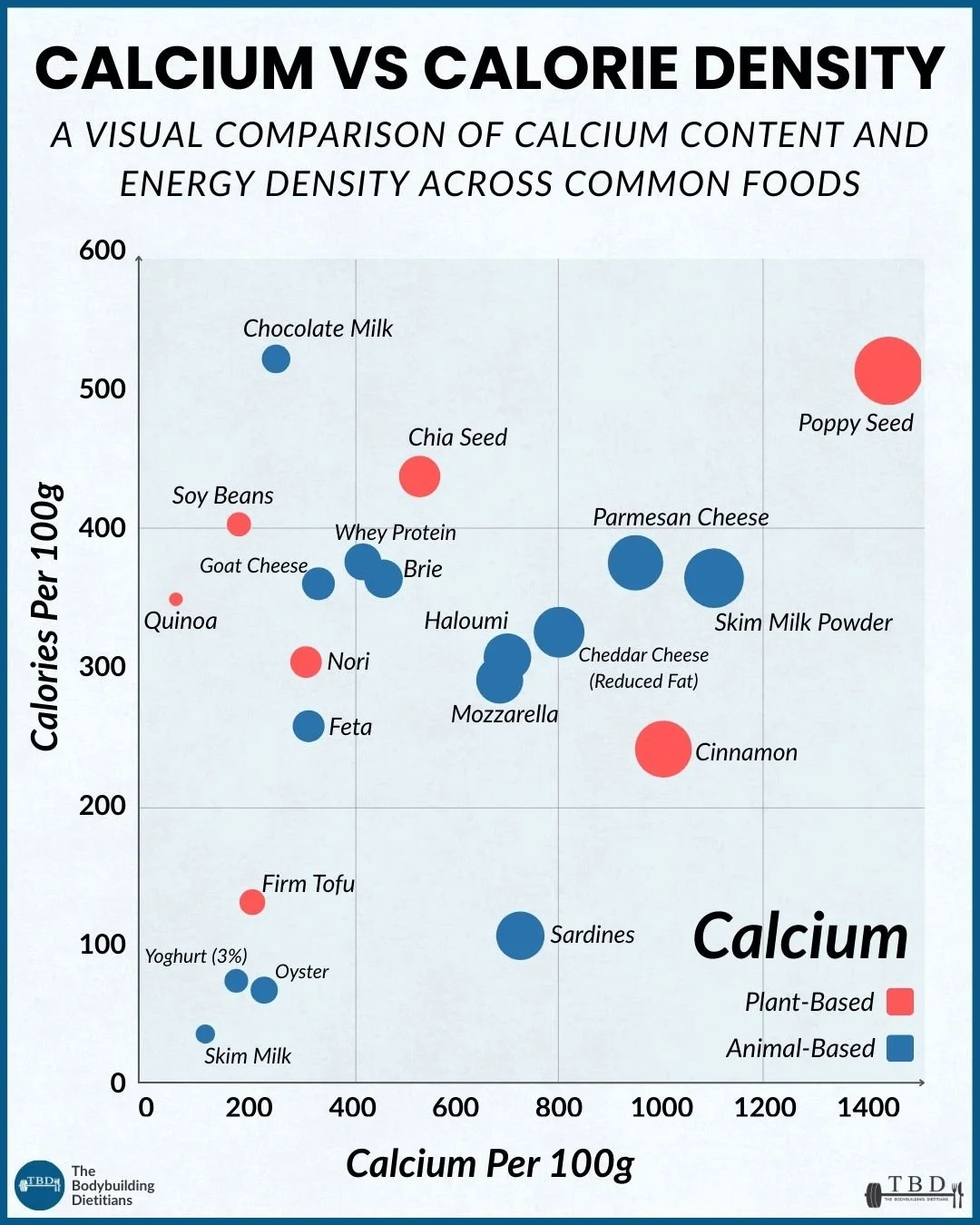

Calcium: Dairy Efficiency and Alternatives

The calcium comparison highlights how calorie trade offs vary substantially across sources.

Dairy products such as parmesan, yoghurt and skim milk powder deliver substantial calcium with relatively efficient calorie profiles. Sardines also provide meaningful calcium alongside protein and other micronutrients.

On the plant side, tofu and chia seeds can contribute meaningfully, though calcium absorption depends on processing methods and the presence of oxalates or phytates. Leafy greens vary considerably, with some offering excellent bioavailability and others less so.

For individuals limiting dairy, achieving adequate calcium intake often requires more deliberate planning.

Emerging Patterns Across All Four Nutrients

When iron, magnesium, zinc and calcium are viewed together against calorie density, several consistent themes appear:

Organ meats and seafood often provide high micronutrient return relative to calories.

Seeds and nuts are repeatedly micronutrient rich but also energy dense.

Legumes and whole grains tend to sit in the middle, offering a blend of fibre and minerals with moderate energy density.

Dairy products, particularly lower fat options, provide efficient calcium delivery.

This does not create a hierarchy of “good” and “bad” foods. Instead, it highlights trade offs.

A food can be highly nutritious and still energy dense. A food can be calorie efficient but limited in certain micronutrients. The goal is not perfection, but awareness.

Context Matters

For someone in a calorie surplus or maintenance phase, energy density may not be a major constraint. For someone in a fat loss phase, every calorie carries more weight.

In those contexts, thinking about micronutrient return per calorie can make the difference between a diet that is merely calorie compliant and one that is both calorie controlled and nutritionally robust.

This becomes particularly relevant in long dieting phases, where cumulative micronutrient shortfalls can influence performance, recovery and overall wellbeing.

Practical Application

You do not need to eliminate energy dense foods to optimise micronutrient intake.

Instead, consider anchoring your diet around foods that provide strong nutrient return relative to calories, then layering in additional options according to preference, cultural pattern and overall energy needs.

A well structured diet often blends:

Efficient animal sources for iron and zinc

Dairy or fortified alternatives for calcium

Legumes, whole grains and seeds for magnesium and additional minerals

Fruit and vegetables to support overall micronutrient diversity

When the base is solid, flexibility becomes easier.

Micronutrient density is rarely discussed with the same intensity as calories or protein. Yet over the long term, it meaningfully shapes performance, recovery and health.

Understanding how iron, magnesium, zinc and calcium relate to calorie density provides a more complete framework for food selection.

If you want support building a nutrition structure that balances energy targets with micronutrient adequacy, our team can help you design an approach that supports both body composition and long term performance.