Foods Ranked by Satiety: What Actually Makes a Calorie Deficit Easier

Most people assume fat loss is primarily about hitting the right calorie number. In practice, what determines success is how manageable that number feels day after day.

Two diets can contain the same calories and macros, yet feel completely different in terms of hunger, cravings and sustainability. The difference is usually food selection.

Your food choices largely determine how hungry you feel in a calorie deficit. And hunger, more than knowledge, determines adherence.

Why Satiety Matters More Than People Realise

Managing hunger is one of the central challenges of sustainable fat loss. When hunger is persistently high, decision-making becomes more reactive, cravings feel more intense, and consistency becomes harder to maintain.

In coaching practice, this shows up clearly. Some individuals report steady energy, stable appetite and predictable routines during a deficit. Others describe constant food focus, frequent snacking urges and difficulty sticking to their plan, even when calories are technically appropriate.

The difference is rarely discipline. It is usually structure.

Satiety refers to how full and satisfied a food makes you feel relative to its calorie content. While individual responses vary, consistent patterns emerge across research and real-world dieting.

What Increases Satiety?

The original Satiety Index research by Holt and colleagues compared how different foods affected fullness relative to white bread. Since then, broader research and practical experience have reinforced several key factors.

Satiety tends to increase with:

1. Higher Protein Content

Protein is consistently the most satiating macronutrient. It slows gastric emptying, influences appetite-regulating hormones and generally makes meals feel more substantial. Diets that anchor meals around adequate protein typically feel easier to sustain.

2. Higher Fibre Intake

Fibre increases fullness by adding bulk, slowing digestion and influencing gut-derived satiety signals. Whole fruits, vegetables, legumes and intact grains tend to perform well here.

3. Greater Food Volume and Water Content

Foods with higher water content and lower energy density allow for larger portions at fewer calories. This increases gastric distension, which contributes to fullness.

4. Lower Energy Density

Energy-dense foods deliver more calories in smaller volumes. While they are not inherently problematic, they provide fewer satiety signals per calorie, which can make it easier to overshoot intake when dieting.

These factors often overlap. Foods that combine several of these characteristics tend to sit higher on the satiety spectrum.

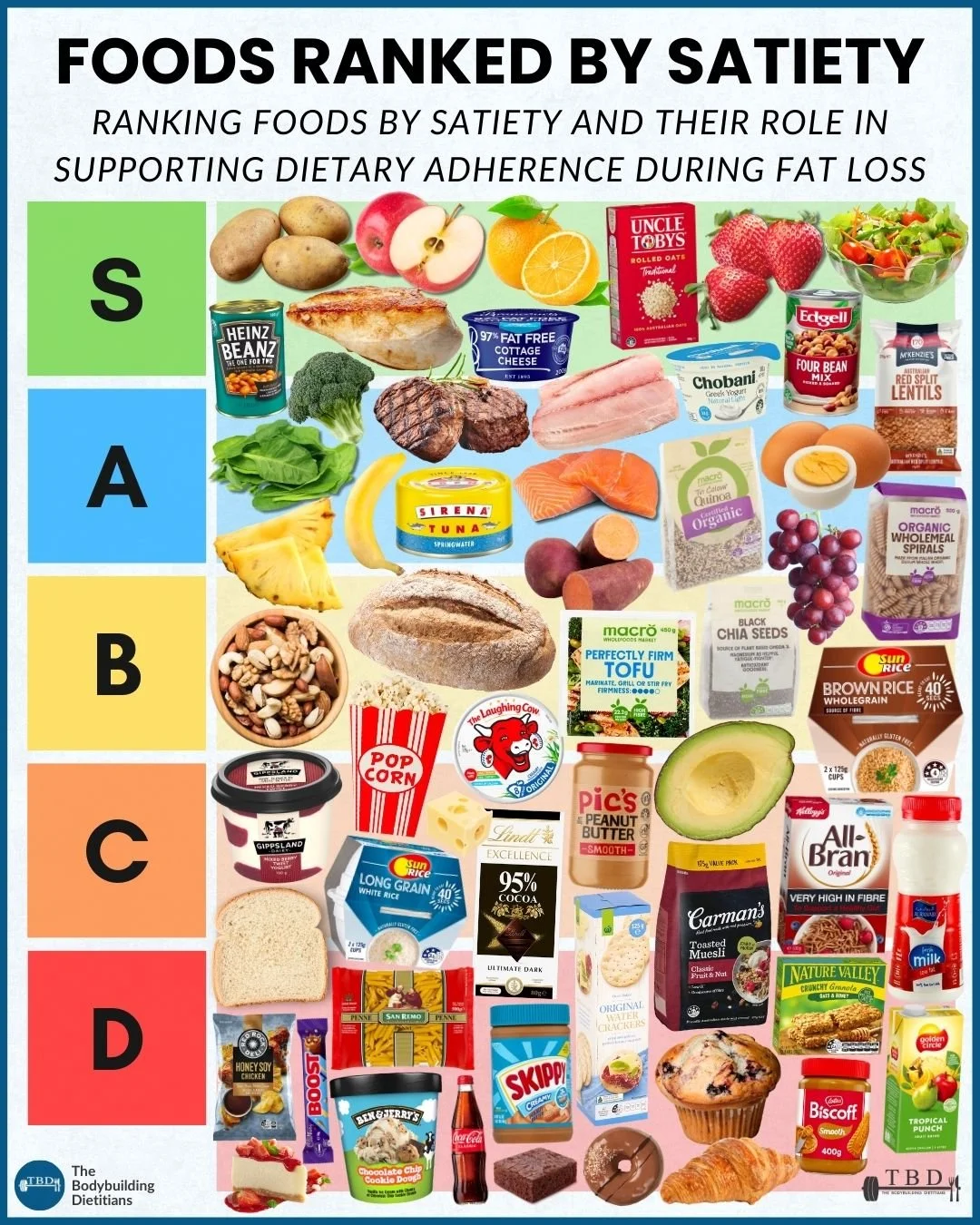

The Satiety Spectrum

Rather than categorising foods as good or bad, it is more useful to view them along a spectrum.

Higher-Satiety Foods

These foods generally provide strong fullness signals relative to their calorie content:

Boiled or baked potatoes

Lean meats and fish

Greek yoghurt and cottage cheese

Legumes and lentils

Oats

High-fibre fruits and vegetables

They tend to combine protein, fibre, water and lower energy density. For many people, building meals around these foods makes a calorie deficit feel significantly more manageable.

Moderate-Satiety Foods

These foods can work well in appropriate portions, especially when combined with protein and fibre:

Rice and pasta

Bread

Nuts and seeds

Dark chocolate

Peanut butter

They are not problematic, but they are easier to overconsume if eaten in isolation.

Lower-Satiety Foods

Highly processed, energy-dense foods often deliver fewer fullness signals relative to calorie load:

Pastries and baked goods

Ice cream

Confectionery

Sugary drinks

Ultra-processed snack foods

These foods can absolutely fit into a balanced diet. The challenge arises when they displace higher-satiety staples during periods where calories are constrained.

Why This Becomes More Important During Fat Loss

When calories are reduced, biological and psychological pressure tends to increase over time. Hunger can rise. Food thoughts become more frequent. Palatable, energy-dense foods can feel more appealing.

This is where food choice becomes strategic rather than incidental.

A diet built primarily around low-satiety foods may technically hit calorie targets, but it often feels unnecessarily difficult. In contrast, a structure anchored in higher-satiety foods tends to create more stable appetite control and fewer reactive eating episodes.

Fat loss is rarely limited by knowledge of calories alone. It is often limited by how well hunger is managed across weeks and months.

Satiety Is Not About Perfection

This does not mean every meal must consist exclusively of the highest-satiety foods.

Rigid restriction often backfires. Flexibility remains important for social situations, enjoyment and long-term sustainability.

The key is proportion. When the majority of intake supports fullness and stability, including more energy-dense foods becomes far easier to manage.

Understanding the satiety spectrum allows you to make deliberate choices rather than reactive ones.

The Bigger Picture

Calories determine weight change. Food choice determines how tolerable that process feels.

If dieting consistently feels harder than it should, the issue may not be your calorie target. It may be the structure of your meals.

Developing a sustainable approach to fat loss involves more than tracking numbers. It involves building meals that work with your physiology rather than against it.

If you would like guidance structuring your nutrition in a way that supports both performance and long-term adherence, our team can help you build a plan that feels manageable, not restrictive.