Training Intensity Is a Skill Most Lifters Never Properly Develop

Most plateaus in hypertrophy aren’t caused by poor programming. They’re caused by lifters consistently stopping their sets too early, often without realising it.

In practice, this usually happens because discomfort is mistaken for proximity to failure. A set starts to burn, breathing gets heavier, the movement feels unpleasant, and the decision to rack the weight feels justified. The problem is that discomfort shows up early. Meaningful mechanical stimulus shows up much later.

Training hard is not defined by how uncomfortable a set feels. It’s defined by how close you are to the point where another high-quality repetition is no longer possible. That distinction matters, because one is emotional and subjective, while the other is physiological and repeatable.

Across coaching experience, this pattern shows up most clearly in lifters who are consistent, motivated, and technically competent, yet frustrated by slow progress. They are showing up, following their program, and putting in effort, but their sets regularly finish with four, five, sometimes six repetitions still left in reserve. Over time, that gap compounds.

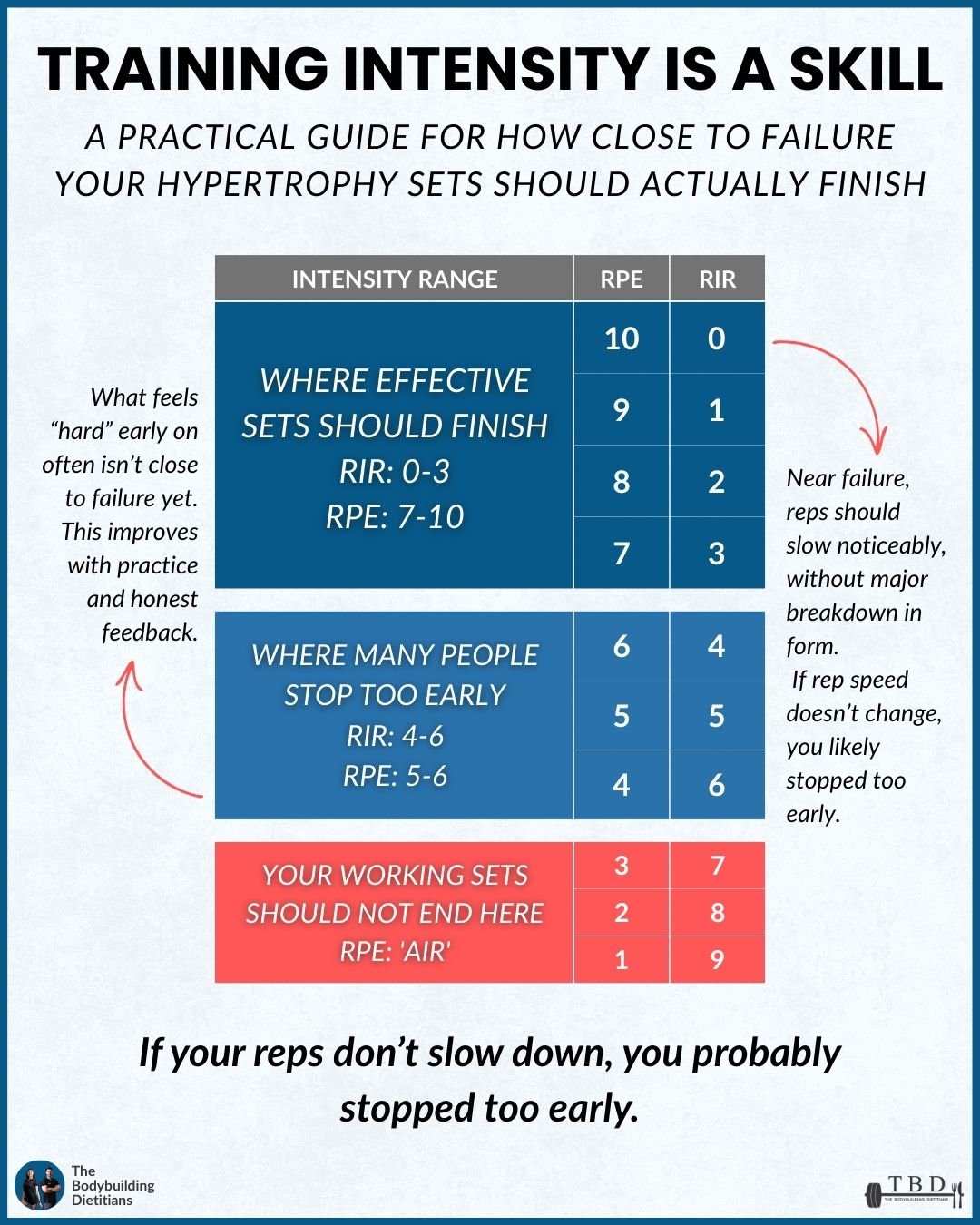

Learning to train in close proximity to true failure is a skill. Like any skill, it requires exposure, repetition, and feedback. Early in a set, reps tend to feel controlled and predictable. As fatigue accumulates, effort rises sharply, rep speed begins to slow, and each repetition demands deliberate intent. The difference between “this is uncomfortable” and “this rep may not move” becomes very clear once you’ve experienced it enough times.

This is where tools like RPE and RIR become useful, not as rigid rules, but as shared language. As perceived effort increases, reps in reserve should fall. For hypertrophy work, the bulk of evidence and practical experience points toward training in the vicinity of zero to three reps in reserve for at least some working sets, provided technique remains stable. Not every set needs to be maximal, and not every exercise demands the same proximity to failure, but regular exposure to that zone is what gives the body a reason to adapt.

In practice, one of the simplest ways to develop this skill is to remove guesswork altogether. Film your sets. Compare the concentric speed of your early repetitions to the final ones. When you are genuinely approaching failure, the reps do not just feel harder, they move differently. A repetition that once took a second now takes several, despite maximal intent to move the load quickly. That visible slowdown is often a more honest indicator than internal perception alone.

What we see repeatedly is that lifters who struggle to make progress often assume they need more volume, more exercises, or more frequent program changes. In reality, they often need fewer changes and more honest execution. If your working sets are ending while the bar speed is still high and movement remains crisp, the issue is unlikely to be recovery, genetics, or program design. More often than not, the stimulus is simply falling short.

Developing the ability to judge effort accurately takes time. It also takes accountability. Training intensity is not something most people learn accidentally. It is refined through feedback, repetition, and a willingness to sit with discomfort long enough to find out where your true limit actually is.

Next time you train, pay attention to the reps that slow down, not just the reps that sting. That is usually where the work that drives adaptation really begins.

Learning to judge training intensity accurately rarely happens by accident. It’s built through structured programming, honest feedback, and long-term oversight that removes guesswork from execution.

If you want support refining how hard you train, not just what you train, our coaching team works closely with athletes to develop these skills over time, so effort consistently translates into progress.