Your Metabolism Isn’t Broken

Many people describe feeling as though their metabolism has been damaged after prolonged dieting or repeated weight loss attempts. In most cases, what they are experiencing is the body responding appropriately to energy availability.

Metabolism is a dynamic and adaptive system. It adjusts according to how much energy you consume, how much you expend, and how much lean tissue you carry. When viewed through this lens, changes in energy expenditure begin to look less like malfunction and more like regulation.

Understanding how this system works creates a far more productive starting point.

What Makes Up Your Total Daily Energy Expenditure?

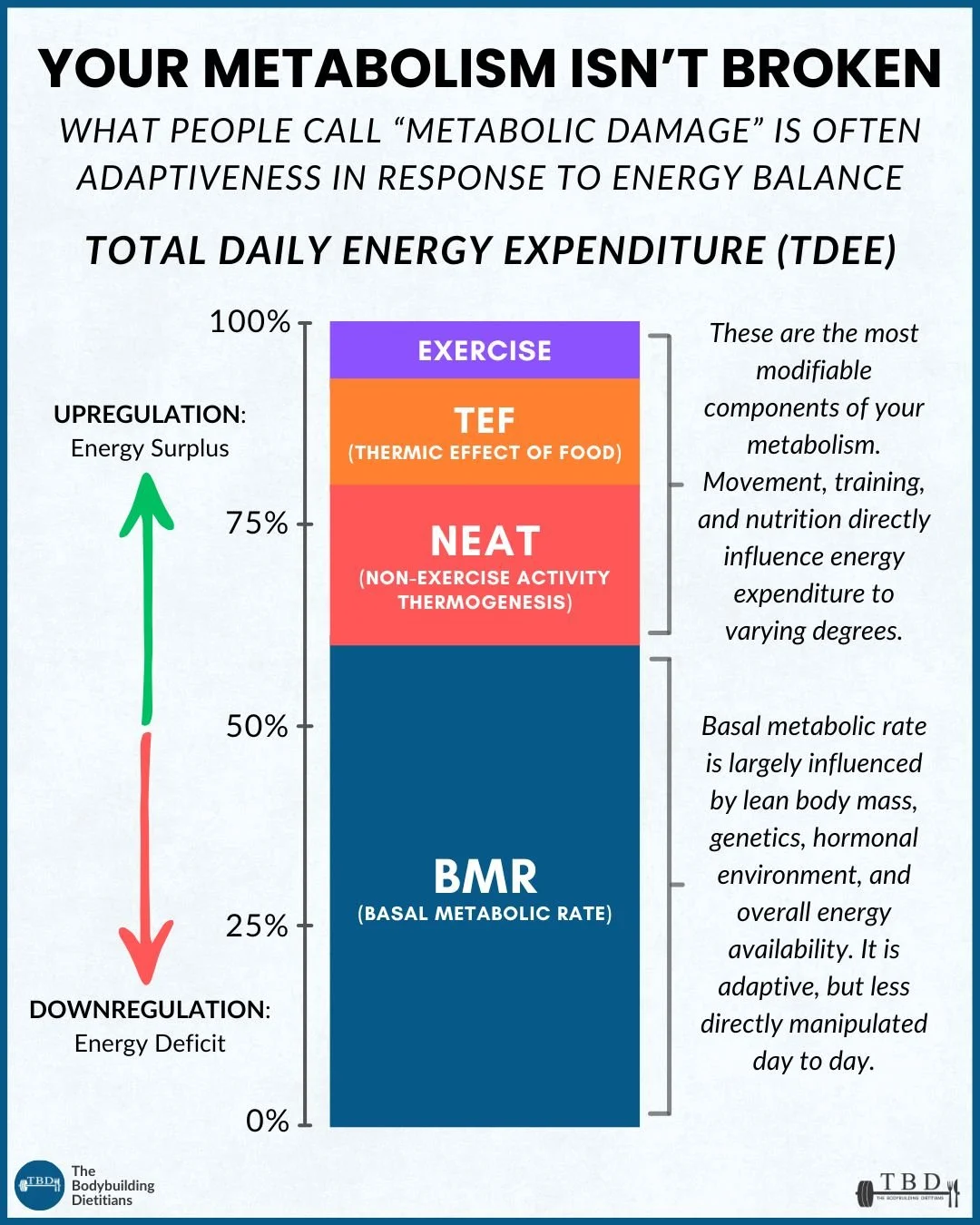

Total daily energy expenditure, often abbreviated as TDEE, reflects the combined energy cost of several components:

Basal metabolic rate (BMR), which represents the energy required to sustain life at rest

Thermic effect of food (TEF), the energy required to digest and process nutrients

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT), which includes daily movement outside of structured training

Exercise, which reflects planned training sessions and sport

Basal metabolic rate typically accounts for the largest portion of total expenditure. It is influenced heavily by lean body mass, genetics, hormonal environment and overall energy availability.

NEAT and exercise are more behaviourally driven and tend to vary considerably between individuals. The thermic effect of food shifts according to both the quantity and composition of the diet, with protein generally requiring more energy to process than carbohydrate or fat.

These components are responsive. They are not fixed.

Adaptation During a Prolonged Energy Deficit

When energy intake is reduced for a sustained period, the body gradually becomes more efficient.

Resting energy expenditure may decline modestly. Spontaneous movement often reduces, sometimes subtly and without conscious awareness. Training performance can soften as recovery resources narrow. The thermic effect of food decreases simply because less food is being processed.

These changes represent conservation rather than dysfunction.

From a physiological standpoint, prolonged energy restriction signals scarcity. Efficiency becomes protective. As efficiency increases, total daily energy expenditure narrows, and the rate of fat loss may slow even if calorie intake remains controlled.

This pattern is common in extended dieting phases and is one reason progress often feels easier at the beginning than later on.

Adaptation Also Occurs in the Opposite Direction

The same system that conserves during restriction can expand when energy availability increases.

When intake rises appropriately and is paired with progressive resistance training, spontaneous movement often increases. Training output improves. Recovery becomes more robust. The thermic effect of food rises alongside greater intake. Lean mass can increase, which supports a higher resting energy requirement.

Energy expenditure is therefore influenced by environment and behaviour over time.

This bidirectional responsiveness is a core feature of human metabolism.

Lean Mass and Metabolic Capacity

Lean body mass remains one of the most significant determinants of resting energy expenditure. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, and maintaining or increasing it supports overall metabolic output.

When individuals engage in aggressive dieting without adequate protein intake or resistance training, muscle loss can occur alongside fat loss. In those situations, reductions in metabolic rate may be more pronounced than expected.

A slower, structured approach that prioritises muscle retention tends to preserve metabolic capacity more effectively. Over months and years, this difference becomes meaningful.

Age, Behaviour and Perceived DECREASE

It is common for people to attribute weight gain or stalled fat loss to age alone. While ageing does bring physiological changes, large-scale data suggest that resting metabolic rate remains relatively stable through much of adulthood.

More substantial changes often relate to behaviour.

Daily movement tends to decline as occupational and lifestyle patterns shift. Resistance training may be inconsistent. Lean mass can gradually decrease. Dietary patterns may include more energy-dense, highly processed foods with lower thermic effect.

The body responds to these environmental inputs.

Framing the issue solely as age-related decline can obscure the modifiable variables that meaningfully influence energy expenditure.

Why the “Metabolic Damage” Idea Persists

When weight loss slows despite continued effort, frustration is understandable. Without context, the experience can feel unpredictable or unfair.

In practice, plateaus often involve a combination of factors:

Reduced spontaneous movement

Subtle increases in energy intake

Decreases in training output

Accumulated fatigue

Heightened appetite signals

These shifts are often gradual, which makes them harder to detect without structured oversight.

Describing the situation as permanent damage can create a sense of inevitability. Viewing it as adaptation encourages strategy.

A More Useful Way to Think About Metabolism

Metabolism can be thought of as a responsive regulatory system that calibrates itself according to long-term energy trends.

Consistent underfeeding and reduced movement encourage conservation. Progressive training, adequate fuelling and maintained lean mass support greater energy turnover.

Neither state is permanent. Both reflect adaptation.

When individuals align training, nutrition and daily movement with their goals over sustained periods, the system adjusts accordingly.

The Broader Perspective

Metabolic adaptation is not trivial, and it can meaningfully influence the rate and experience of fat loss. However, it is rarely irreversible.

A structured approach that considers lean mass preservation, adequate protein intake, training stimulus and realistic calorie targets tends to produce far more stable outcomes than cycles of aggressive restriction and rebound.

When progress feels stalled, the solution is usually found in recalibration rather than resignation.

If you would like guidance designing a nutrition and training structure that works with metabolic adaptation rather than reacting to it, our team can help you build a plan grounded in physiology and long-term sustainability.