How to Actually Read Nutrition Labels (Without Letting Them Make Decisions for You)

Nutrition labels are often treated as the final authority on whether a food is “good” or “bad”. In reality, they are a reference tool, not a prescription.

Used properly, nutrition panels can help you compare products, estimate energy intake, and understand how certain foods fit into your broader diet. Used poorly, they can create confusion, unnecessary restriction, and an overemphasis on numbers that matter far less than people think.

The goal is not to memorise labels or obsess over every line. It is to understand what information is useful, what is contextual, and what is largely marketing noise.

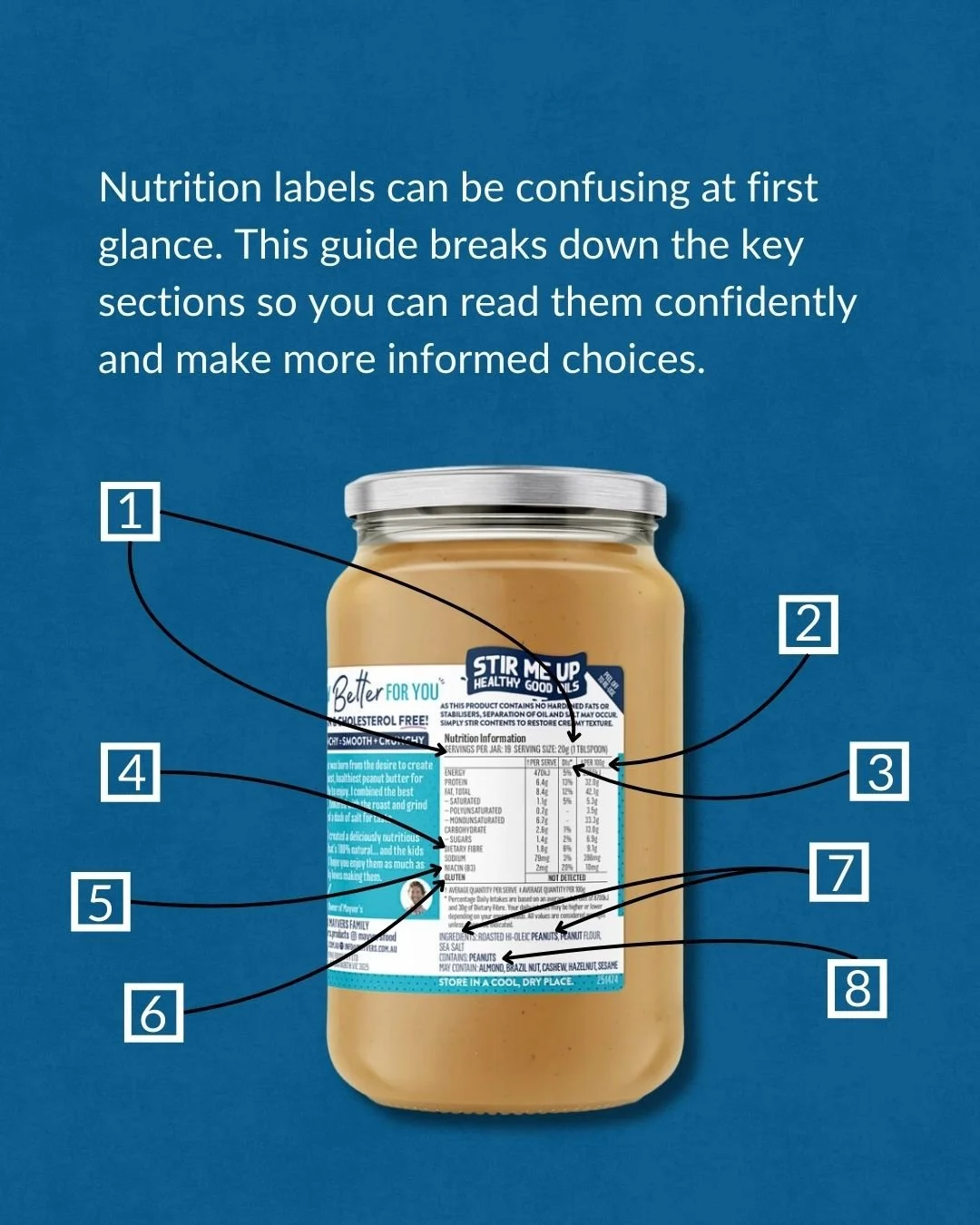

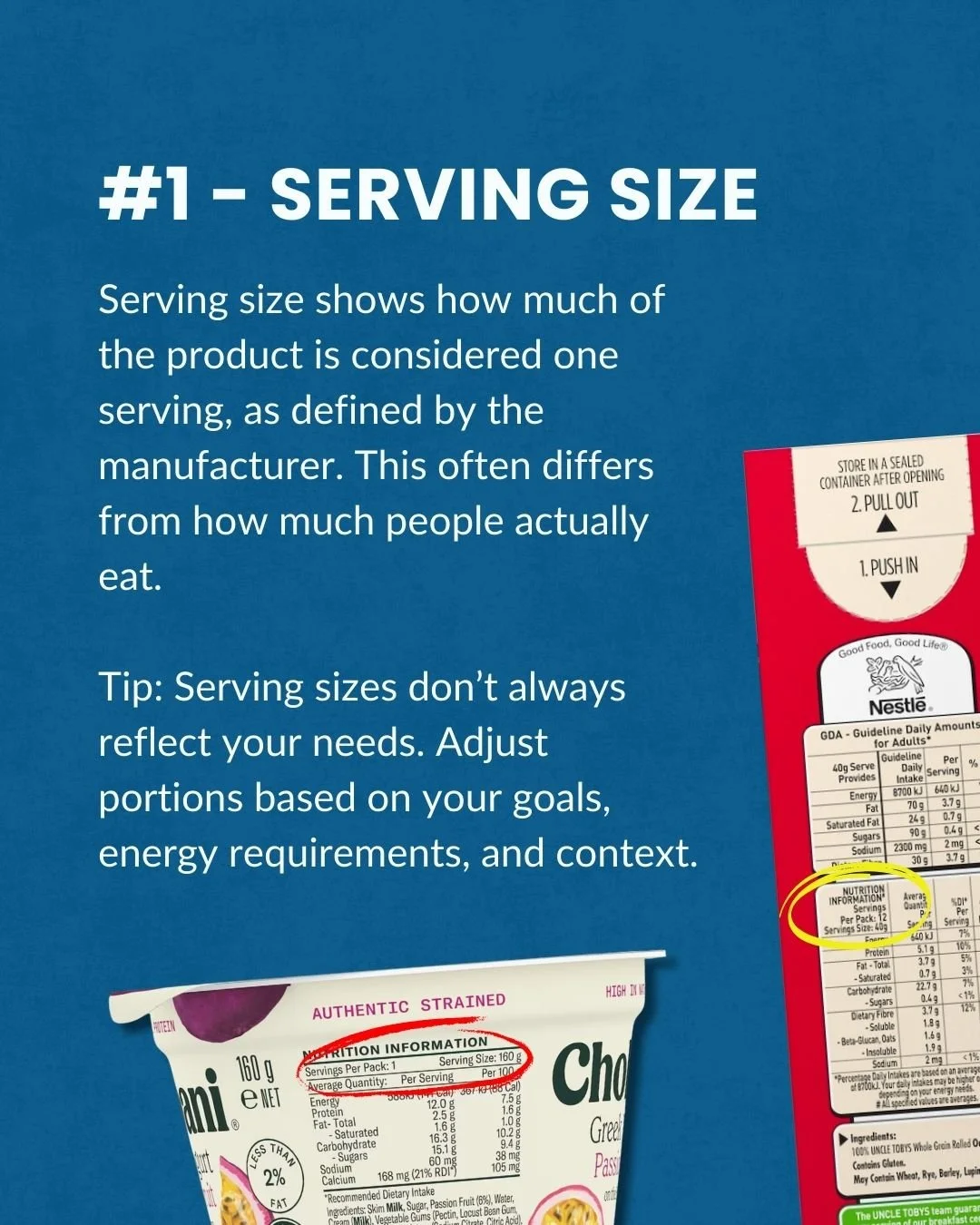

Serving size is a reference, not a recommendation

The serving size listed on a nutrition panel reflects what the manufacturer defines as one serve. It does not reflect what most people actually eat, nor does it reflect what you personally need.

This matters because every value on the panel is anchored to that serving size. Energy, protein, fat, sugars, fibre, and sodium can all appear deceptively low when the serving size is unrealistically small.

Rather than asking whether a food “fits” based on the listed serve, it is more useful to ask how much you realistically consume and how that portion contributes to your total intake across the day.

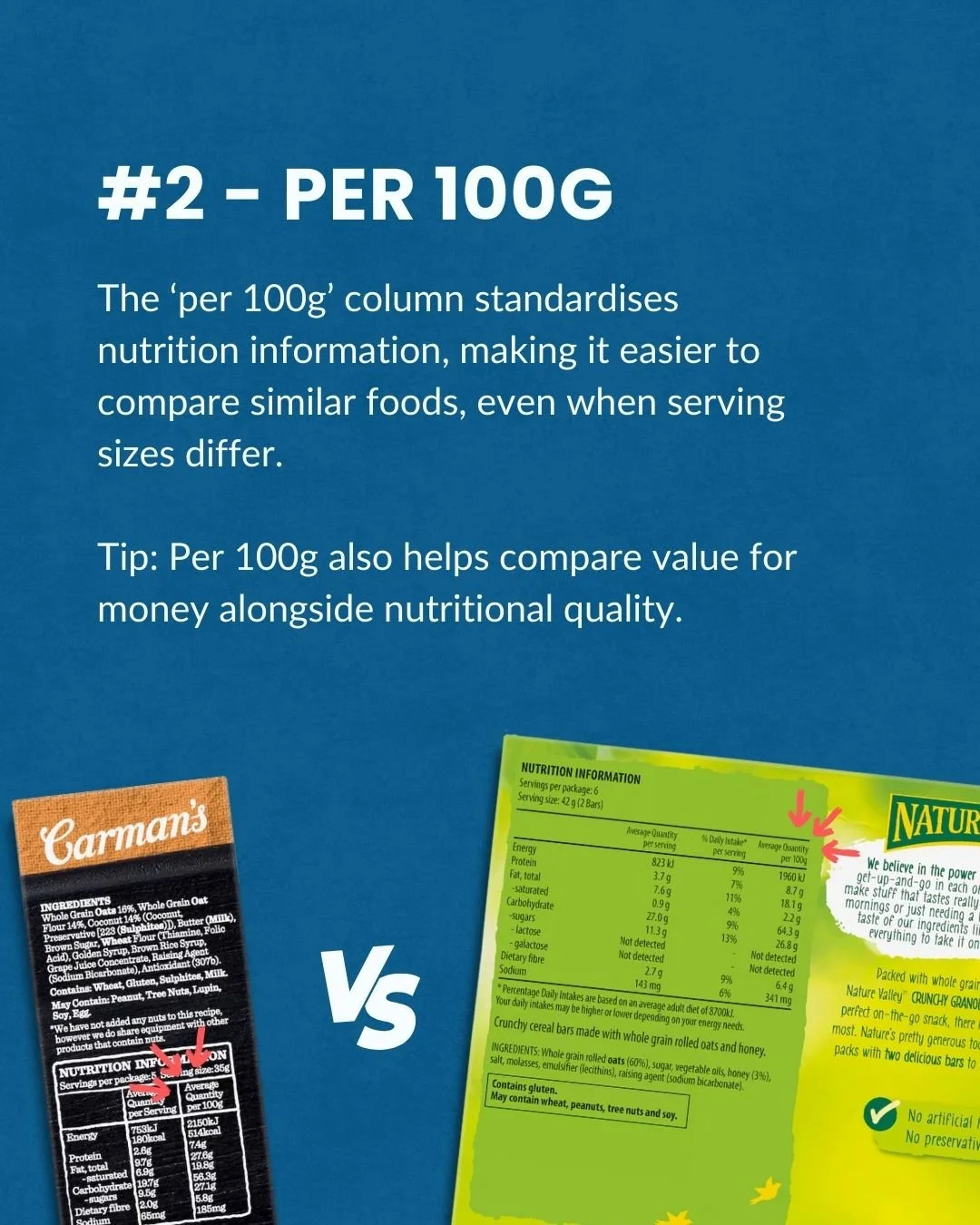

The per 100 g column is where comparisons actually happen

If you are comparing two similar foods, the per 100 g column is usually the most informative part of the label.

It removes serving size manipulation and allows you to compare energy density, protein content, fibre, sugars, and fat on an equal footing. It also makes it easier to compare value for money alongside nutritional quality.

For most packaged foods, this column tells you far more than the per-serve numbers ever will.

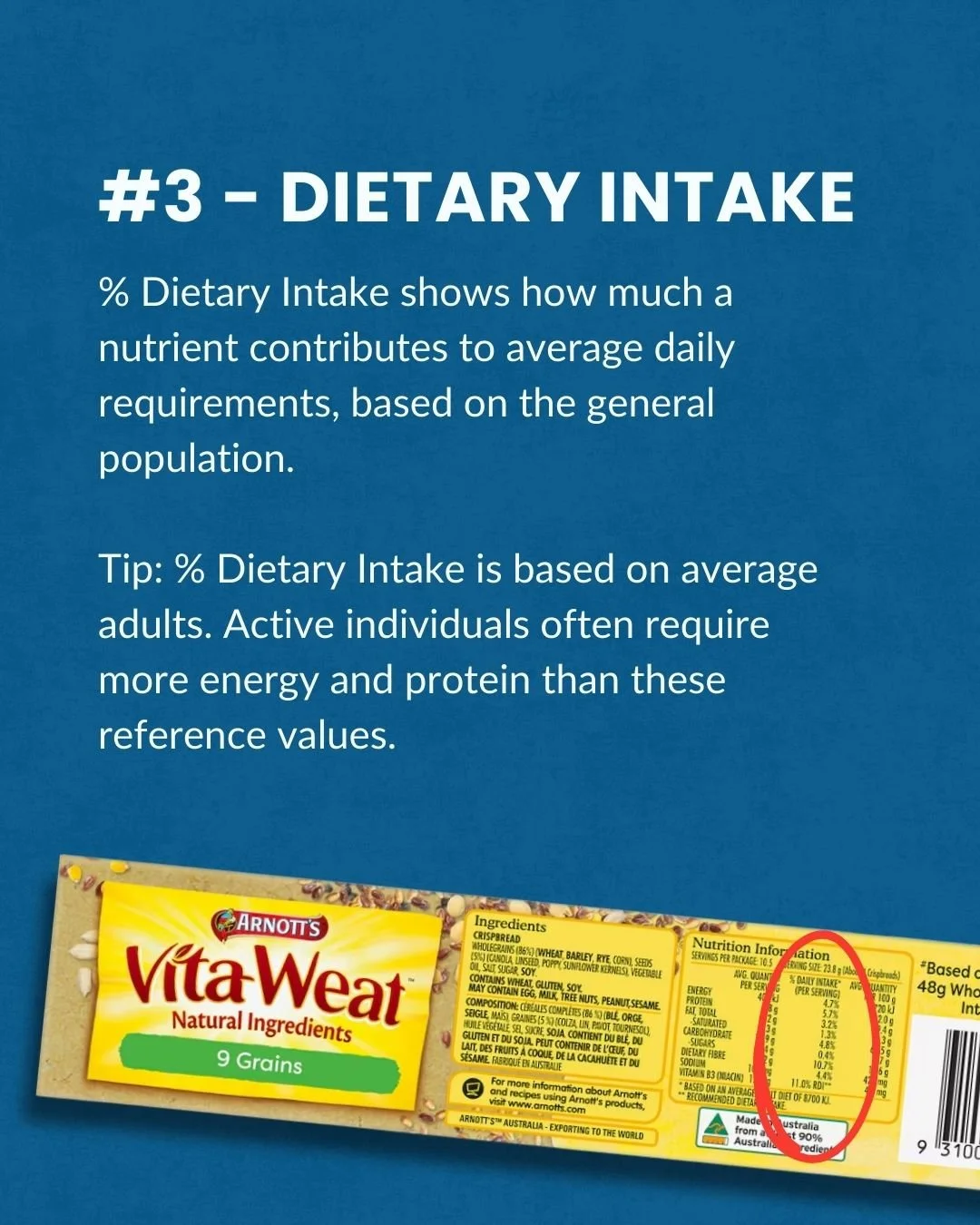

Percentage daily intake needs context

Percentage daily intake values are based on the needs of an average adult consuming around 8,700 kJ per day. They are not tailored to active individuals, athletes, or people with higher energy and protein requirements.

This means a food that appears to provide a small percentage of daily protein may actually be a meaningful contributor for someone training regularly, while a food that appears “high” in a nutrient may be less relevant in the context of the rest of the day.

These values are best treated as rough reference points, not targets to hit or avoid.

Fibre is useful, but not always obvious

Dietary fibre is one of the more useful numbers on a nutrition panel, particularly for satiety and digestive health. However, fibre is not always listed unless a product makes a fibre-related claim.

Checking grams of fibre per serve or per 100 g can help identify foods that contribute meaningfully to overall fibre intake, but it should not replace a broader focus on whole foods like vegetables, fruits, legumes, and wholegrains.

A product being “high in fibre” does not automatically make it a good choice, just as a product being low in fibre does not automatically make it a poor one.

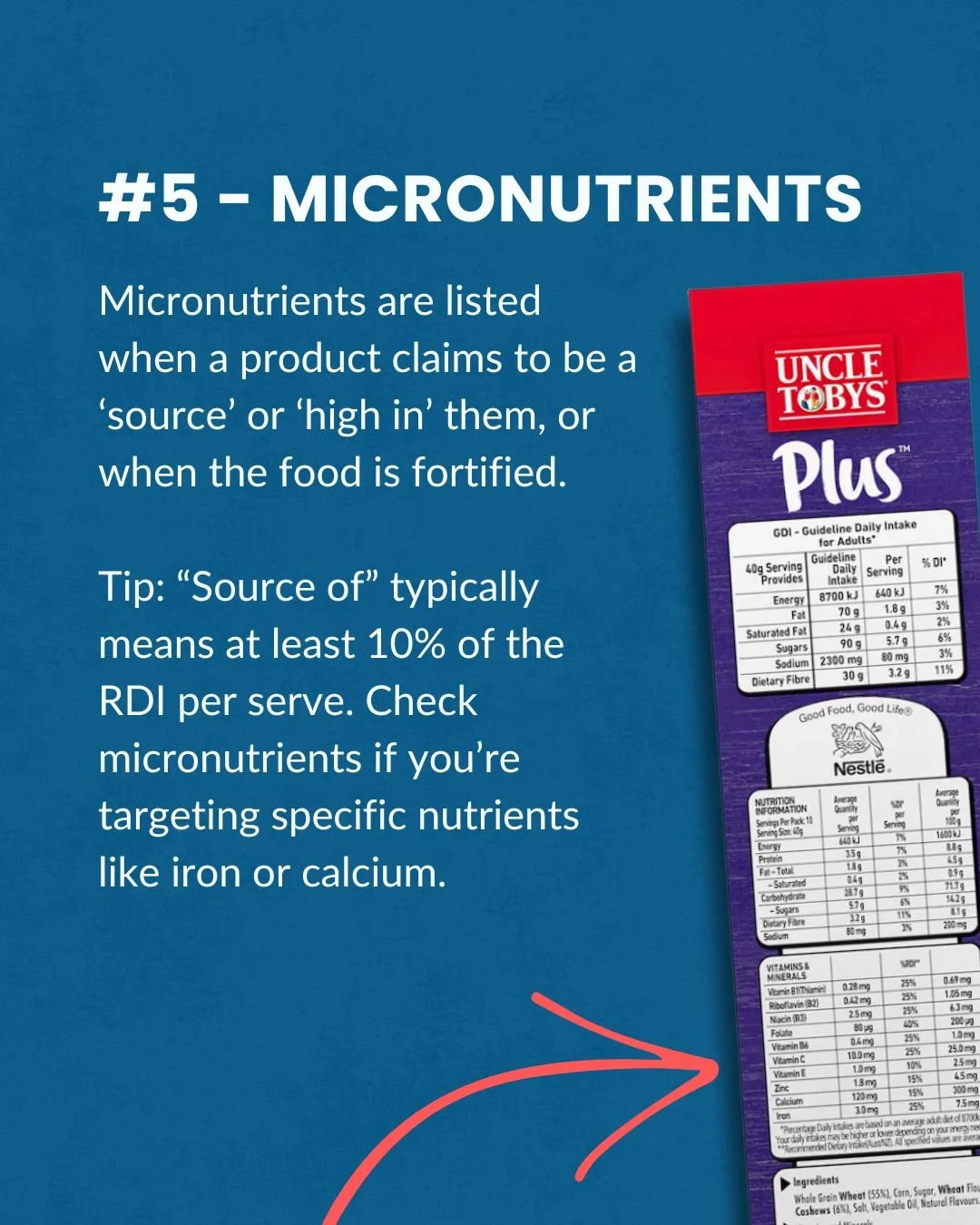

Micronutrients are conditional information

Micronutrients only appear on labels when a food claims to be a source of them or has been fortified. Their absence does not mean a food lacks nutritional value, and their presence does not mean a food is essential.

If you are targeting specific nutrients such as iron, calcium, or iodine, labels can help narrow options. Outside of that context, micronutrient panels are rarely the deciding factor in food choice.

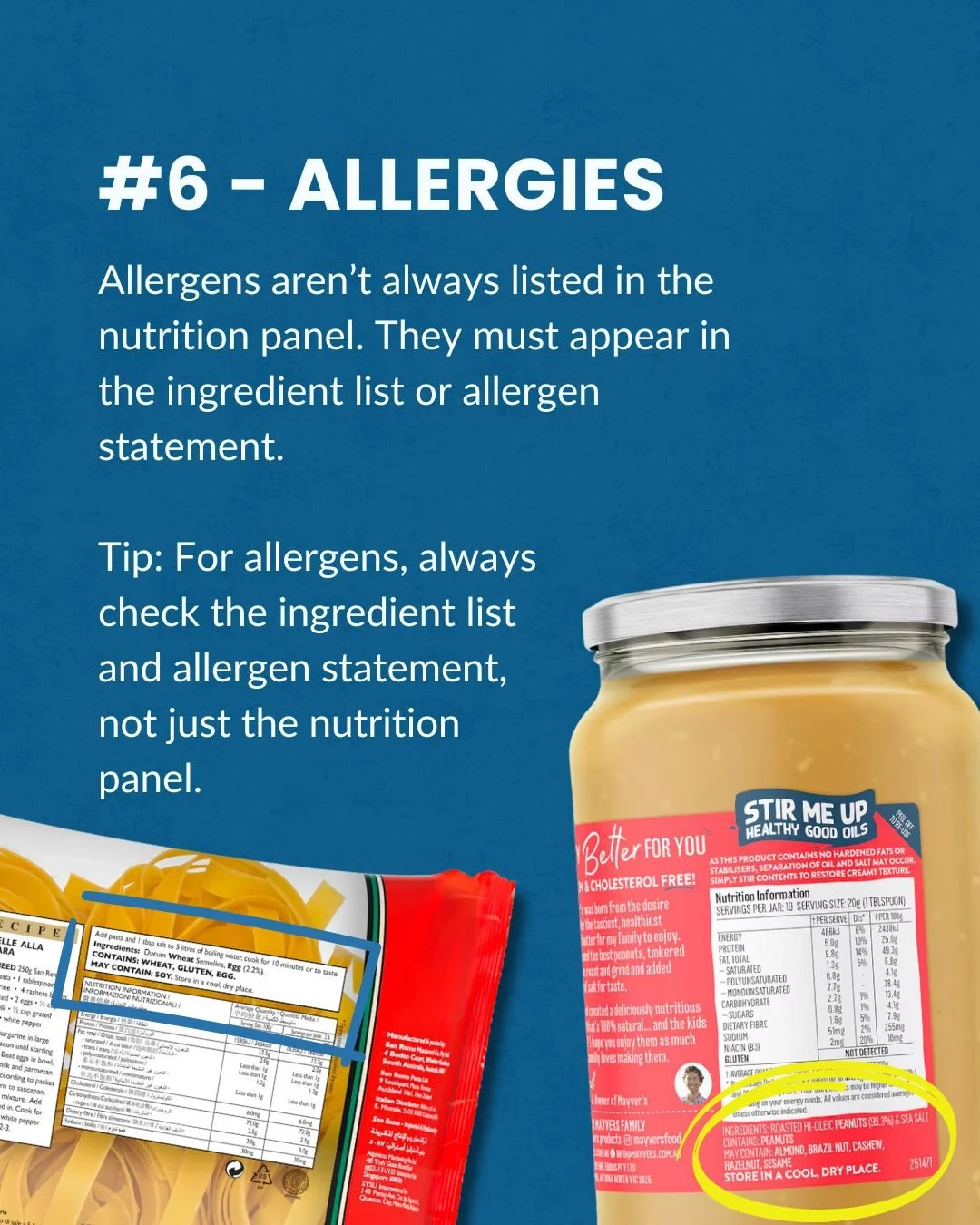

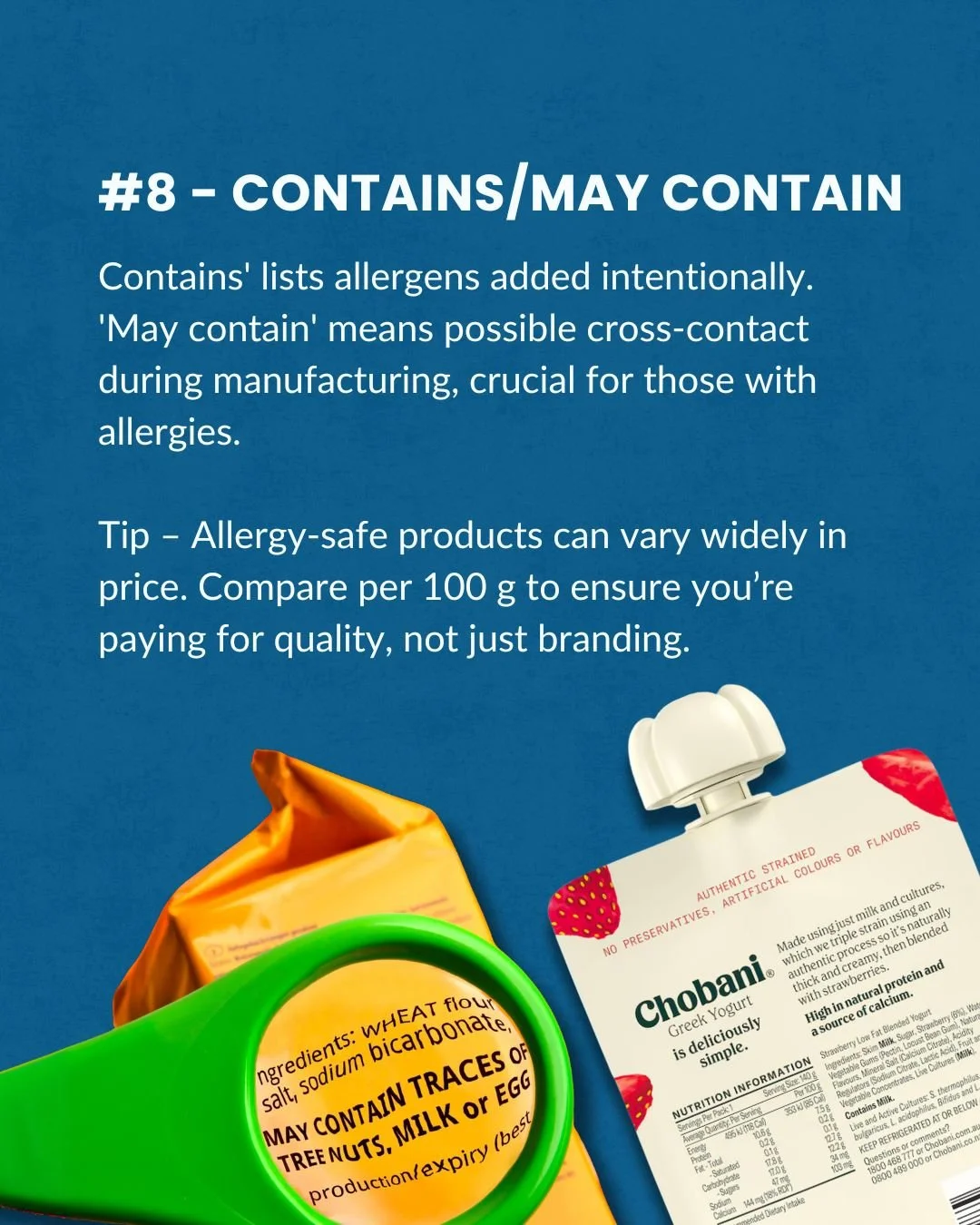

Allergens live outside the nutrition panel

Allergen information is not part of the nutrition panel itself. It appears in the ingredient list or allergen statement.

“Contains” refers to ingredients intentionally added, while “may contain” reflects possible cross-contact during manufacturing. For people with allergies, this distinction matters far more than anything else on the label.

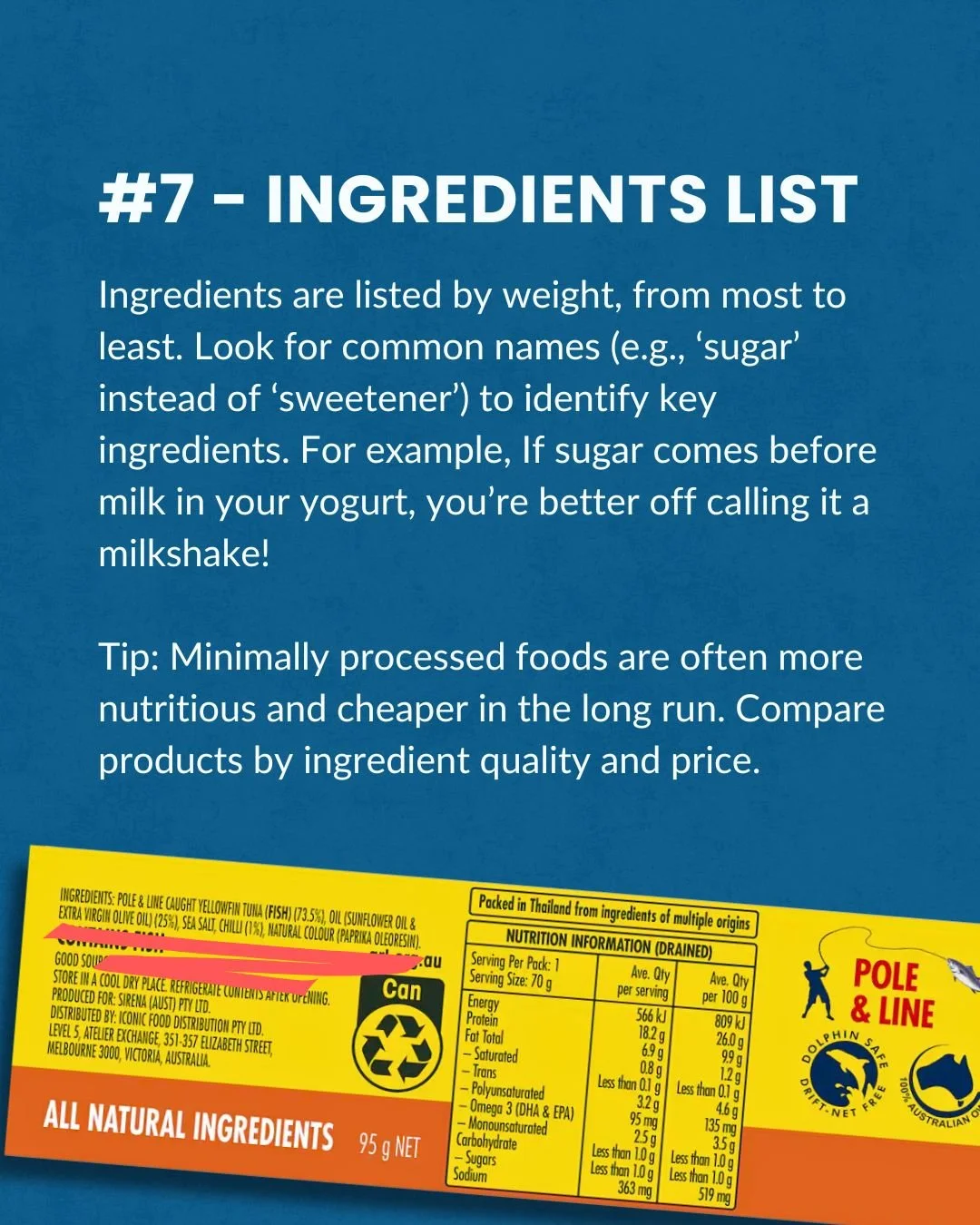

Ingredients lists reveal priorities, not morality

Ingredients are listed from most to least by weight. This helps you identify what a product is primarily made of, rather than what is highlighted on the front of the packet.

This is useful for understanding processing level, added sugars, and ingredient quality, but it still needs to be interpreted in context. A longer ingredients list is not inherently bad, and a shorter one is not inherently good.

What matters is how the product fits into your overall dietary pattern, not whether it passes a simplistic ingredients test.

Labels inform decisions, they should not make them

Nutrition panels do not account for food quality, satiety, enjoyment, cultural context, or how foods interact across a full day of eating. They also do not reflect individual needs, training demands, or long-term adherence.

Used well, labels support informed choices. Used rigidly, they outsource decision-making and often create unnecessary stress around food.

The most effective approach is to treat nutrition labels as one input, not the deciding factor.

If you want support applying this kind of thinking to your own nutrition, training phases, or lifestyle context, our coaching focuses on decision-making, not food rules.