Why a Food-First Approach Doesn’t Make Sense for Creatine

A food-first approach to nutrition is generally a sound principle. Prioritising whole foods supports micronutrient intake, appetite regulation, gut health, and long-term adherence. In most contexts, it’s a sensible default.

Creatine, however, is one of the clearer exceptions.

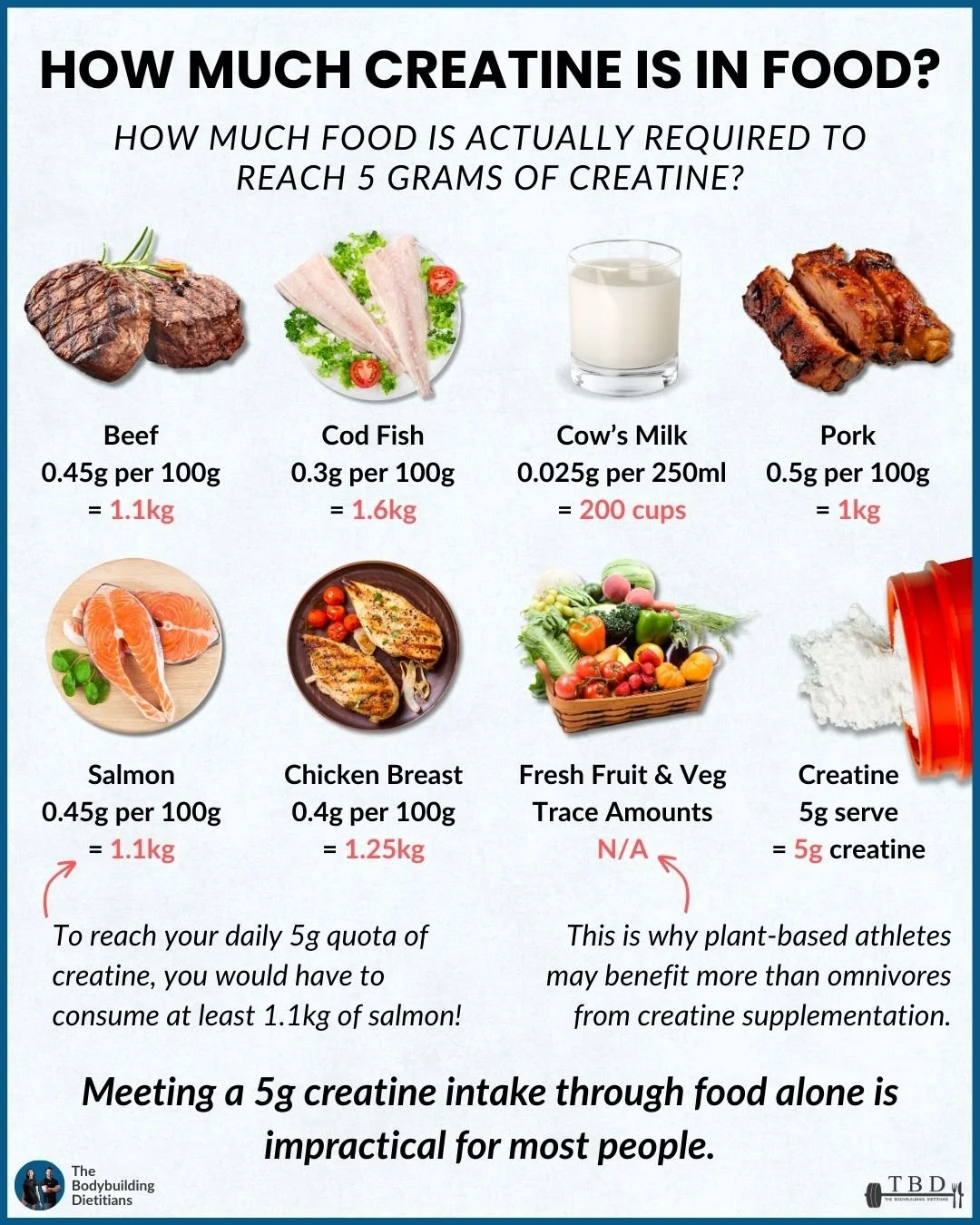

While it is technically possible to obtain creatine from food, the gap between theoretical intake and practical application is substantial. Animal products such as red meat and fish contain creatine, but the concentrations are relatively low. Reaching a clinically effective intake of around 5 grams per day through diet alone would require consuming quantities of food that are unrealistic for most people on a consistent basis.

As illustrated in the accompanying graphic, this could mean eating over a kilogram of salmon or beef per day, or drinking hundreds of cups of milk. Beyond the obvious impracticality, this approach brings with it a large and unnecessary load of calories, protein, fat, fluid, cost, and digestive demand that are unrelated to creatine itself. In other words, the collateral intake quickly becomes the limiting factor.

This is where supplementation shifts from being optional to simply rational.

Five grams of creatine monohydrate provides a precise, isolated dose of the compound without forcing excessive energy intake or compromising dietary flexibility. Rather than complicating the nutrition plan, supplementation in this case simplifies it. The goal is not to replace food, but to avoid distorting the diet in pursuit of a single nutrient that is difficult to obtain efficiently through whole foods.

There is also a practical nuance that often gets overlooked. Creatine is heat-sensitive. Cooking meat reduces its creatine content, meaning the values typically cited for raw foods tend to overestimate what is actually delivered on the plate. This further widens the gap between what looks achievable on paper and what is realistically consumed.

From an evidence standpoint, creatine remains one of the most robustly studied supplements available. Its benefits for strength, power output, and lean mass accretion are well established. More recently, research has continued to highlight potential cognitive benefits, particularly in situations involving sleep deprivation, high mental demand, or heavy training loads. For individuals balancing training, work, and limited recovery, these effects are not trivial.

In some contexts, higher intakes may be used strategically, such as doses closer to 10 grams per day. That doesn’t imply that more is always better, but it does further reinforce how impractical a food-only approach becomes once intake moves beyond baseline levels.

None of this diminishes the importance of diet quality. Food still provides the foundation for performance, health, and recovery. But when a compound is safe, inexpensive, extensively researched, and difficult to obtain in meaningful doses from whole foods, supplementation is not a shortcut. It is simply the most efficient tool for the job.

A food-first mindset works best when it is applied with context, not dogma. Creatine is a useful reminder that good nutrition is less about rigid rules and more about choosing the right approach for the outcome you’re trying to achieve.

Note: food quantities shown refer to uncooked weights. Cooking further reduces creatine content, meaning even larger amounts would be required to reach equivalent intakes.

If you’re trying to balance performance, recovery, and long-term health without turning nutrition into a logistical burden, having clarity around when food matters most and when supplementation is appropriate can make a significant difference.

If you’d like support integrating evidence-based strategies into a broader training and nutrition framework that actually fits your lifestyle, our team is here to help.