Post-Workout Nutrition Doesn’t Need to Be Complicated

Most athletes do not stall because their post-workout nutrition is “wrong.” They stall because they either overthink it to the point of paralysis or underthink it entirely, bouncing between rigid rules and complete neglect depending on what they last heard online.

In practice, what your body needs after training is remarkably consistent across lifters, phases, and experience levels. The mistake is assuming that complexity equals effectiveness, when in reality, reliable progress usually comes from repeatedly executing a small number of fundamentals well.

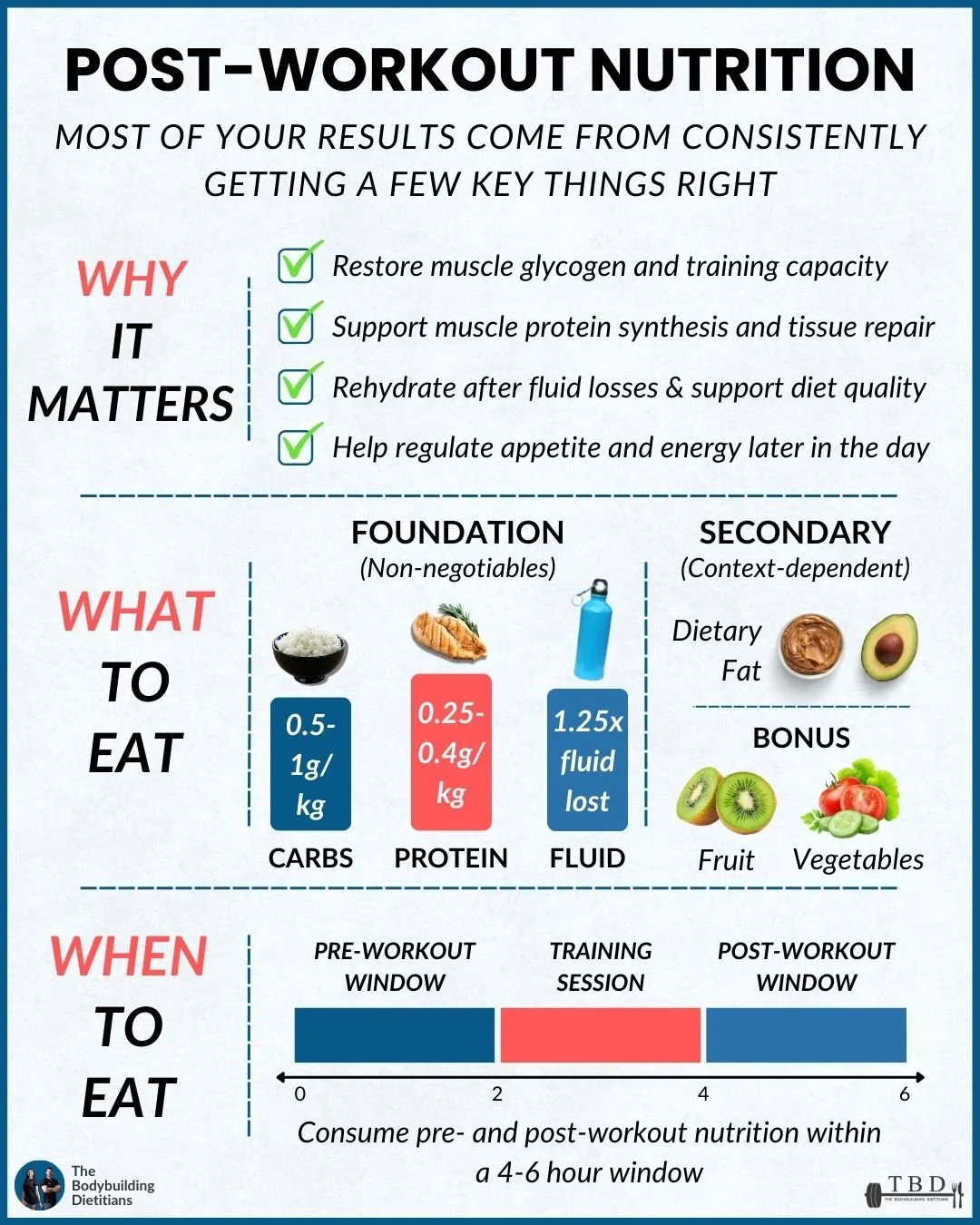

At its core, post-training nutrition exists to do four things: replenish some of the fuel you used, support muscle repair, replace fluid losses, and help regulate appetite and energy for the rest of the day. Once those needs are met, most of the marginal debate becomes largely irrelevant.

Why Post-Workout Intake Actually Matters

Resistance training creates a unique combination of muscular stress and metabolic demand. While it is not as glycogen-depleting as endurance work, it still draws on carbohydrate stores, elevates protein turnover, and increases fluid loss through sweat. When those demands are not addressed, recovery becomes slower, subsequent training quality suffers, and appetite regulation later in the day often becomes harder than it needs to be.

In our coaching experience, athletes who consistently struggle with evening overeating, poor session-to-session performance, or a general sense of “flatness” often have less of a calorie problem and more of a poorly timed fueling problem earlier in the day.

Post-workout nutrition does not need to be perfect, but it does need to be intentional enough to support the work you’ve just done.

The Non-Negotiables: Carbohydrate, Protein, and Fluid

For most lifters, carbohydrate intake in the range of approximately 0.5 to 1 gram per kilogram of bodyweight post-training is both practical and sufficient. Resistance training does not empty muscle glycogen stores in the way long-duration cardio does, so there is flexibility here. Athletes with higher daily carbohydrate targets, multiple sessions per day, or particularly high training volumes may sit toward the upper end of that range, but there is rarely a need to force intake beyond what fits the broader day.

Protein intake of roughly 0.25 to 0.4 grams per kilogram reliably provides enough essential amino acids, including leucine, to stimulate muscle protein synthesis in most individuals. Consuming more protein than this is not inherently problematic, particularly for athletes with higher daily protein requirements, but there is little advantage in chasing excessively large doses under the assumption that more is automatically better.

Fluid replacement is often the most overlooked component. The general guideline of replacing around 1.25 times the fluid lost during training simply accounts for continued losses after the session ends. For athletes who do not track sweat loss, which is entirely reasonable, a practical rule of thumb is to consume roughly 500 to 750 millilitres per hour of training, then continue drinking gradually until urine colour returns closer to baseline.

These three elements form the foundation. When they are in place consistently, most post-workout nutrition concerns resolve themselves.

The Contextual Pieces: Fat, Fibre, and Food Quality

Dietary fat does not need to be avoided after training unless there is a very specific reason to prioritise rapid digestion, such as back-to-back sessions. For athletes training once per day, including fat in the post-workout meal does not meaningfully impair recovery and often improves satiety and meal satisfaction.

Fibre, fruit, and vegetables are also not enemies in this window. In fact, for athletes eating three to four meals per day, the post-workout meal often represents a large proportion of total daily intake. That makes it an efficient opportunity to reinforce overall diet quality, micronutrient intake, and gut health rather than relying on later meals to “fix” the day.

The idea that post-workout nutrition must be bland, liquid, or surgically precise tends to create unnecessary rigidity without delivering meaningful benefit.

Thinking in Windows, Not Moments

One of the most common sources of confusion is treating post-workout nutrition as a narrow, fragile window that must be exploited perfectly. A more useful framework is to think in terms of a broader peri-workout period, spanning roughly four to six hours across pre-, intra-, and post-training intake.

When nutrition is distributed sensibly across that window, the pressure on any single meal diminishes. Missed precision becomes far less consequential, adherence improves, and fueling feels more like part of a normal eating pattern rather than a ritual that requires constant vigilance.

In practice, athletes who adopt this wider perspective tend to be more consistent, less anxious around timing, and better able to sustain their approach across long training phases.

Keep the Focus Where It Belongs

Post-workout nutrition works best when it supports the bigger picture rather than competing with it. It should reinforce training quality, recovery, and appetite control without becoming another source of stress or over-analysis.

Get the basics right often enough, and the returns compound quietly over time.

Developing an effective nutrition strategy is rarely about finding new rules. It is about applying the right ones consistently, in a way that fits your training demands, lifestyle, and long-term goals.

If you want guidance that helps you integrate training and nutrition into a system you can sustain, our team works with athletes to build structured, evidence-based approaches that hold up over time.